Bumbarash

1971

Ukrainian SSR

Oleksandr Dovzhenko Film Studio

127 min

Mykola Rasheiev

Yevhen Mytko

Vitalii Zymovets, Borys Miasnykov

Valerii Zolotukhin, Yurii Smirnov, Nataliia Dmitriieva, Aleksandr Khochinskii, Oleksandr Belyna, Ekaterina Vasileva, Lev Durov, Leonid Bakshtaev, Roman Tkachuk, Nikolai Dupak, Marharyta Krynytsyna, Aleksandr Filippenko

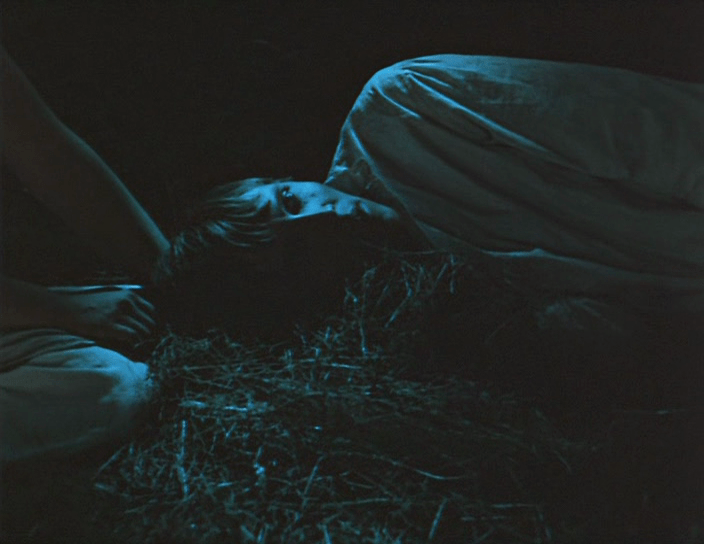

Bumbarash (this is not a nickname – it’s a surname), an ordinary private in the meat grinder of the First World War, gets on a hot air balloon, is captured by the Austrians, and then finds his way to his native village where he is considered dead. Bumbarash’s girl, Varia, has already married Havrylo, the bandit. The spirited hero wants to win back his love and a civilian serene life, but gets drawn into military confrontation between several gangs and armies, including the Bolsheviks, who were destined to win.

The poetics of Kyiv’s director Mykola Rasheiev, who with Bumbarash achieved a one-time Soviet Union-wide fame, sharply differs from the baroque ethnography of his colleagues from the Dovzhenko Studio of the 1960s-70s. However, his choice of theme seems to connect him not only with Russian like-minded individuals—Gleb Panfilov, Alexander Askoldov, and especially Gennady Poloka—but also with Ivan Mykolaichuk’s Babylon XX (and to some extent with Hryhorii Kokhan, Yurii Illienko), who similarly conducted a moderate revision of the narrative of establishing Soviet power, without completely rejecting a revolutionary pathos. All the mentioned directors from different studios developed this theme under the threat of censorship. In the case of Bumbarash the television format saved it from collecting dust on the shelves.

Rasheiev (formally listed in the credits Abram Narodytskyi didn’t shot a single scene in the film) refers to the primary source of Soviet patriotic legends—the prose of Arkadii Gaidar, the most famous “popularizer” of events from the turn of the 1910s-20s. Bumbarash uses Gaidar’s plots but presents the “civil war” in the quite refashioned territory of Ukraine/Kuban (shot in Cherkasy region) as a tragicomedy saturated with music and blood; the director borrows artistic means from FEKS and other personas of the old-school Soviet avant-garde but through the Moscow’s sixties’ bohemian culture with their bardic poetry and the theater at Taganka. From a contemporary perspective, in this tale (or perhaps part thereof) devoid of morals and a happy ending, one can see either the glorification of the Soviet myth or its denial ad absurdum. But primarily, it vividly outlines the essence of this myth—a cruel, wild, dehumanizing force that, unlike the ideological superstructure, happily survived the collapse of the Union.