Biosphere! Time for Consciousness / Biosfera! Chas usvidomlennia

1974

Ukrainian SSR, Kyivnaukfilm

16 min

Feliks Soboliev

Vladen Kuznietsov

Heorhii Lemeshev, Mykola Mandrych, Petro Rakityn, Volodymyr Bielorussov

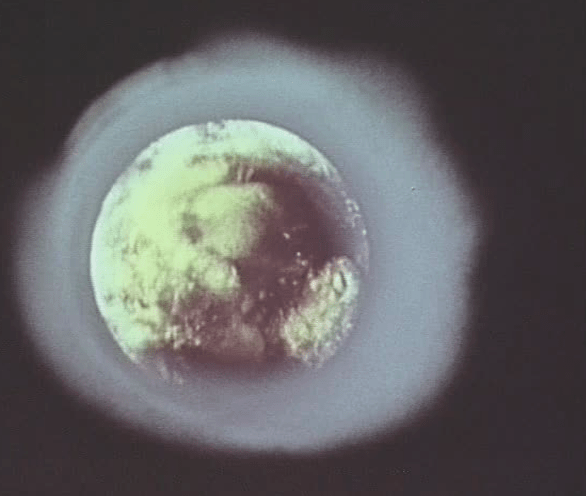

The film is inspired by the work of Volodymyr Vernadskyi. It is a journalistic narrative that explores the genesis of life in the universe, from the physical elements of the primordial soup to the civilization of Homo sapiens. Biosphere! Time of Awareness (1974) is, in some ways, a groundbreaking manifesto film that marks a division in the filmography of Feliks Soboliev, the guru of the Kyiv School of popular science cinema.

While in the late 1960s, Soboliev was interested in cybernetics and the technological revolution, gaining fame with polemical films about scientific mysteries and experiments (The Language of Animals, 1967), by the second half of the 1970s, his focus had shifted to themes that contemporary science still struggled with, primarily the boundaries of human consciousness and the depths of the subconscious. This interest sometimes went beyond illustrating scientific wonders and worn-out Soviet humanistic realism, carrying a powerful emancipative motif. Zinaida Furmanova, the author of the first Soviet book about Soboliev, wrote: “Long before April 1985, Soviet people were granted permission to see, hear, and speak.” She suggested that Soboliev showed us that we are all conformists (I and Others, 1971), but we have incredible potential (Seven Steps Beyond the Horizon, 1969; Dare, You Are Talented, 1974).

Biosphere! Time of Awareness briskly takes humanity beyond the confines of its daily life and its Sovietness. It urges our minds to transcend individual or group thinking. Whether returning to Vernadskyi or anticipating the future, it invites us to think on a planetary scale. Naturally, the film still carries the burden of 20th-century anthropocentrism — evident both in placing humans at the pinnacle of evolution and in the strong voice of the rational male narrator. Despite this, the film not only sifts through the best ideas of “noosphere theory” and the Soviet version of the New Age but also offers concepts relevant to 19th-century ecological thinking. In the film’s metaphor of life as a random icy crystal on a windowpane, Soboliev even seems to prefigure the ideas of physicist-cosmologist Lawrence Maxwell Krauss.

The film’s aesthetics also deserve special attention. Illustrating cells or physical elements in a rather free animated style, Soboliev creates one of the few Soviet films whose level of poetics and abstractness resonates with the Western avant-garde cinema of that time.