Interpretation of Dreams / Tlumachennia snovydin

1990

Ukrainian SSR, Austriia, Kyivnaukfilm, Chetver, ORF

52 min

Andrii Zahdanskyi

Semen Vinokur

Volodymyr Huievskyi

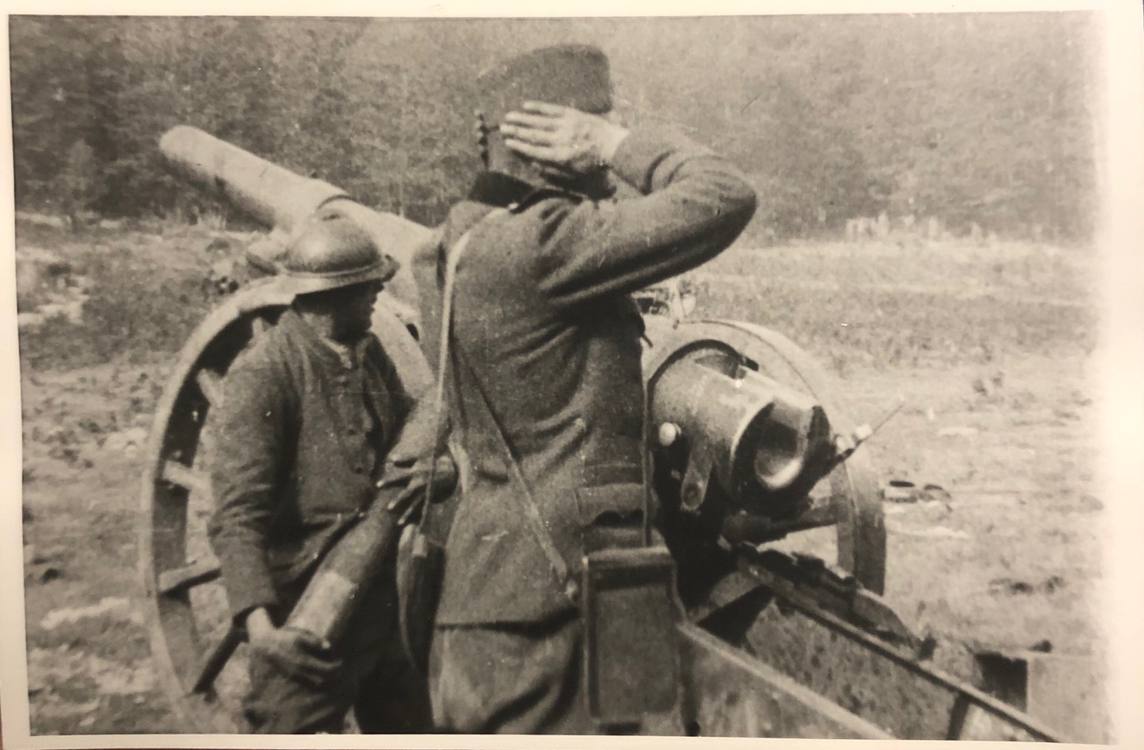

In the documentary film Interpretation of Dreams, director Andrii Zahdanskyi invites viewers to revisit the chronicle of events in the first half of the 20th century in the form of an intrusive dream. And to analyze the dream, its symbols, and underlying forces through a dialogue with Sigmund Freud, the founder of psychoanalysis. The director attempts to find explanations for these crucial phenomena in the history of the 20th century within psychoanalytic theory. Notably, the years covered by the film’s chronicle are limited to two significant dates — 1896 and 1939 — reflecting events contemporary to Freud. In 1896, Freud began working on his first fundamental text, The Interpretation of Dreams, where he introduced the concept of the “unconscious,” while the Lumière brothers demonstrated their first film, which is considered the invention of cinema. In September 1939, Freud passed away in London after moving from Vienna following the annexation of Austria by Nazi Germany; the same month marked the beginning of World War II.

The film’s chronicle is combined with footage shot in the late 1980s in Vienna, the birthplace of the psychoanalyst. Desolate rooms with subdued light, frames with photos, and mirrors on the walls serve as the space where a therapeutic session could take place. Off-screen, similar to a doctor’s appointment, only two voices are heard: the voice of the director Andrii Zahdanskyi and the voice of Sigmund Freud portrayed by the renowned Soviet actor Sergey Yursky, known for roles like Ostap Bender and the director in The Republic of ShKID.

The film emerged during the years of Perestroika when censorship restrictions waned, and the themes in movies started to surface from the depths of the unconscious, with eros and thanatos being the most commercially profitable. Instead of joining this carnival of permissiveness, Zahdanskyi attempts to find tools in psychoanalytic theory to explain not only contemporary reality but also the preceding decades of totalitarian experience. Although the film is dedicated to events at the beginning of the 20th century, it fluently speaks about the late Soviet era with its interest in psychoanalysis (Freud’s works were not published in the USSR from 1928 to 1989) and about the policy of Glasnost, which allowed addressing the traumas of the stormy 20th century.

The film received acclaim at festivals and served as a ticket for the director to immigrate to the United States, where it was shown at the Jewish Film Festival in San Francisco in 1991. “The director puts the entire country on the couch for analysis, securing the support of Sigmund Freud as a guide,” writes The New York Times about the film.